The Enigmatic Storyteller: Edward Hopper’s Cinematic Vision

In the realm of visual storytelling, few artists have left as indelible a mark as Edward Hopper. His paintings, with their haunting compositions, evocative lighting, and mysterious narratives, have captivated audiences for decades. For filmmakers seeking to elevate their craft, Hopper’s work offers a masterclass in the art of cinematic storytelling, providing invaluable lessons on framing, atmosphere, and the power of suggestion.

Recently I spent an evening with Hopper’s work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan. If you have never been, it is well worth a visit and if you’re lucky, you can take advantage of free Fridays or alternating Free Sundays. The experience will leave you inspired and, if you are like me, a devout fan. The Whitney’s Biennial is currently in circulation and the mixed media and visual storytelling presented this year are unlike any other. But I digress, and return now to Hopper and cinematic storytelling.

Note: I have taken some inspiration from the recent PBS American Masters program on Edward Hopper. HOPPER: An American love story premiered this year on PBS and was produced by an old colleague of mine from my A+E network days, Michael Casio. For more on that and another look at Hopper’s relationship to movies, check out their article: Edward Hopper and the movies | American Masters | PBS. My reflection assumes you as a reader have heard of Edward Hopper or in some way have been introduced to his work. So, I’ll get right into it.

Framing the Voyeuristic Gaze

One of Hopper’s most distinctive techniques is his use of unconventional framing and viewpoints, which create a sense of voyeurism and detachment. Works like “Night Shadows” and “New York Movie” position the viewer as an unseen observer, peering into private moments through windows or around corners. (“Night Shadow” reminds me of my time living in Chelsea before it was “safe”, peering out through my window at people passing by. It immediately takes me back.) This voyeuristic perspective mirrors the camera’s role in film noir, where stark angles, harsh lighting contrasts, and distorted spaces evoke a mood of isolation and unease.

Hopper’s fascination with voyeurism and the act of observation can be traced back to his early days as an art student. His instructor, Robert Henri, encouraged him to frequent movie theaters as an exercise in studying human behavior and capturing fleeting moments. This practice not only honed Hopper’s skills as an observer but also fostered his appreciation for the cinematic experience, shaping his artistic vision in profound ways.

Hopper became an avid moviegoer, drawn to the immersive power of the silver screen. He found solace in the darkened theaters, using them as sanctuaries for quiet reflection and inspiration.

Suggestive Storytelling and the Power of Ambiguity

Hopper’s paintings are also masterful exercises in suggestive storytelling, presenting fragments of narratives and leaving clues but no definitive answers. Works like “Nighthawks” and “Office at Night” invite multiple interpretations, compelling the viewer to complete the story in their own mind. This technique of withholding information and fostering ambiguity is a hallmark of great cinema, as it engages audiences and encourages them to actively participate in the storytelling process.

Hopper’s “Office at Night,” 1940, owned by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has led to many conversations about mad men and their escapades ofsex in the city. The painting depicts a man and a woman in an office setting, with the man seated at a desk and the woman standing by a filing cabinet. The composition and the characters’ positioning suggest a complex dynamic between the two figures, leaving the viewer to wonder about the nature of their relationship and the events that may have transpired before or after the captured moment.

Hopper’s intention behind the painting is revealed in a letter he wrote to the Walker, where he stated, “My aim was to try to give the sense of an isolated and lonely office interior rather high in the air with the office furniture which has a very definite meaning for me.” He then briefly discussed the lighting within the painting before adding, “Any more than this, the picture will have to tell, but I hope it will not tell any obvious anecdote, for none is intended.”

Hopper’s embrace of ambiguity and open-ended narratives can likely be traced back to his early days as an illustrator for pulp fiction magazines. In these publications, he developed his ability to capture fleeting moments and imbue them with narrative depth, leaving room for the reader’s imagination to fill in the gaps. This approach would become a defining characteristic of his later work, as he sought to create paintings that resonated with audiences on a visceral level, inviting them to linger and explore the layers of meaning beneath the surface.(spend time at the MoMA or Whitney and you will linger. I do.)

Personally, I have always been captivated by his 1940 piece “Gas.” The setting is an incredible opening frame to a story of suspense and isolation. You can imagine who will drive down that road or stumble out of those woods. The profound silence that fills this place has all the elements for the perfect setting of the next “A Quiet Place” movie.

Atmospheric Lighting and Emotional Resonance

Perhaps Hopper’s most celbrated skill is his use of light and shadow, which not only shapes the physical spaces but also engraves them with psychological weight and emotional resonance. The dramatic lighting in paintings like “Nighthawks” and “House by the Railroad” evokes a sense of alienation and existential solitude, reflecting the human condition in the modern world. (It is no small surprise that “House by the Railroad” evokes thoughts of Norman Bates; more on that later.)

Early in his career, Hopper worked as an illustrator for silent film posters, where he learned to capture the essence of a story through a single image. This experience not only honed his skills in composition and lighting but also deepened his appreciation for the power of visual storytelling. This would later serve as a foundation for his ability to harness light and its transformative effects in his own artwork.

“When I don’t feel in the mood for painting I go to the movies for a week or more. I go on a regular movie binge!”

— Edward Hopper

The Intersection of Art and Cinema

Hopper’s paintings are not mere static images; they are cinematic narratives frozen in time, inviting the viewer to imagine the stories that unfold before and after the captured moment. This intersection of art and cinema is well-exemplified in his work “New York Movie,” where a lone usher stands lost in thought as patrons sit softly illuminated by the flickering light of the screen. I have often wondered what the lone woman was thinking about. You could wager she has seen the film a hundred times and at this moment is off in another time and space of her own making. The painting itself becomes a metaphor for the cinematic experience, inviting the viewer to contemplate the relationship between art and the moving image.

Throughout his career, Hopper maintained a deep appreciation for the art of cinema, often drawing inspiration from the films he watched and incorporating their techniques into his own work. He saw his paintings not as static images but as frozen moments in time, each one a frame in a larger narrative that invited the viewer to imagine the stories that unfolded before and after the captured moment.

The Cinematic Dialogue: Hopper and Hitchcock

While Hopper’s paintings have inspired countless filmmakers, his artistic dialogue with Alfred Hitchcock stands out as particularly profound. The two masters, though working in different mediums, shared a kindred sensibility, capturing the human condition through suggestive narratives and voyeuristic perspectives.

Hitchcock was an avid admirer of Hopper’s work, finding resonance in the painter’s ability to imbue ordinary scenes with a sense of mystery and unease. The framing of Hopper’s canvases, with their strategic use of windows and unconventional viewpoints, mirrored Hitchcock’s own cinematic techniques, inviting the viewer to become a voyeur peering into private moments.

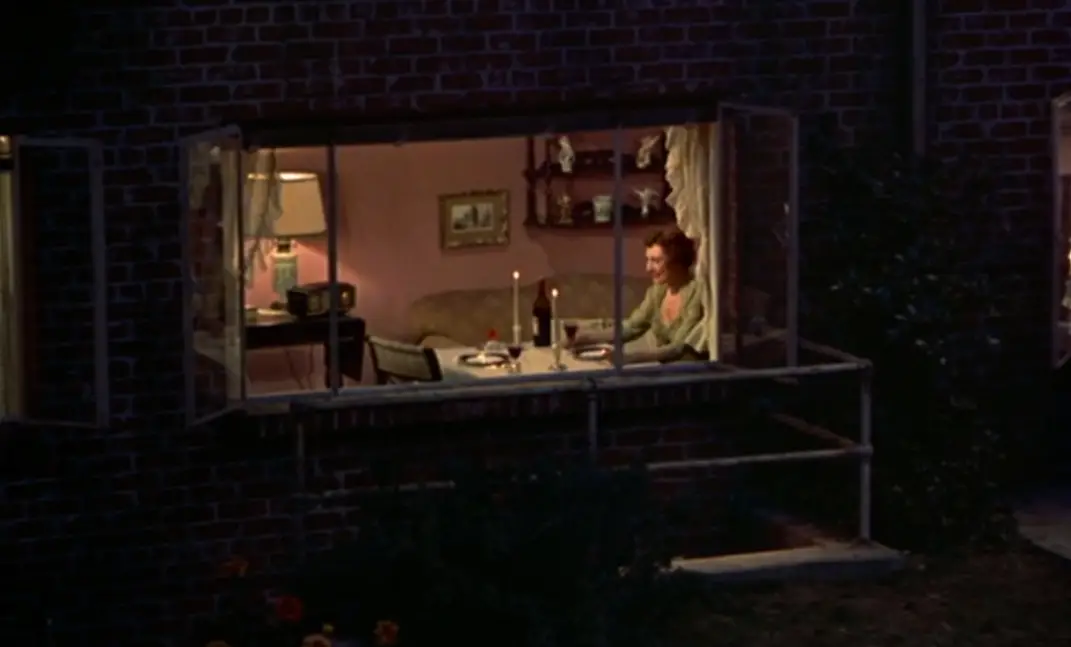

This voyeuristic gaze is perhaps most evident in Hitchcock’s 1954 masterpiece Rear Window, which draws direct inspiration from Hopper’s paintings like “Night Windows” and “Room in New York.” In these works, Hopper frames solitary figures through windows, creating a sense of intrusion and isolation in the midst of dense urban surroundings. Hitchcock translates this voyeuristic perspective to the silver screen, positioning the audience as unseen observers of the lives unfolding across the courtyard.(Still one of my fa²vorite films, Stewart and Kelly!!)

Beyond framing and perspective, Hopper’s influence on Hitchcock deftly extended to the realm of suggestive storytelling and ambiguity. Just as Hopper’s paintings present fragments of narratives, leaving clues but no definitive answers, Hitchcock’s films often withhold information, compelling the audience to fill in the gaps and construct their own interpretations. (I’m still learning and rewatching.)

However, this artistic dialogue was not a one-way street. Hopper, an avid moviegoer himself, was deeply influenced by the emerging film industry and its ability to capture the essence of modern life. He found inspiration in the atmospheric qualities of film noir, adopting its use of chiaroscuro lighting and labyrinthine urban settings in his own canvases. (When I was studying film at NYU, this was alien to me. It wasn’t until I matured as a viewer that I truly appreciated the majestic mystery of it all.)

Hopper and Hitchcock were engaged in a continuous creative exchange, each drawing inspiration from the other’s work while pushing the boundaries of their respective mediums. Their shared fascination with voyeurism, isolation, and the human condition transcended the limitations of canvas and celluloid, creating a dialogue that continues to resonate with audiences and artists alike.

The artistic dialogue between Edward Hopper and Alfred Hitchcock stands as a testament to the enduring influence of Hopper’s cinematic vision. Their shared exploration of the human experience through the lens of voyeurism and ambiguity has left an indelible mark on the world of visual storytelling, inspiring generations of filmmakers and artists to delve deeper into the mysteries of the human condition.

A Legacy of Cinematic Storytelling

Edward Hopper’s paintings, with their masterful use of framing, suggestive narratives, atmospheric lighting, and the seamless blending of art and cinema, have solidified his place as one of the most influential visual storytellers of the 20th century. His work not only captures the essence of the American experience but also invites us to contemplate the universal themes that bind us together.

As I reflect on Hopper’s extraordinary contributions to the world of art and cinema, it becomes clear that his legacy extends far beyond the confines of his canvases. His paintings are more than static images; they are living, breathing narratives that continue to captivate and inspire audiences across generations.

Through his unmatched ability to intertwine the ordinary with mystery and meaning, Edward Hopper has forever altered the landscape of visual storytelling. His influence can be seen in the works of countless filmmakers, from the haunting compositions of David Lynch to the intimate character studies of Wim Wenders.

In the end, Edward Hopper’s contribution to the world of cinema is not confined to the flickering images of the silver screen. His true legacy lies in the way he taught us to see the world anew, to find meaning and beauty in the everyday, and to embrace the power of visual storytelling to illuminate the human condition. As long as there are those who seek to explore the mysteries of the human experience through the lens of art and cinema, Edward Hopper’s influence will continue to shine as a guiding light, inspiring us to see the world through his singular, cinematic vision.